Three of the six information industries gained jobs in June and job losses slowed in the other three industries, according to preliminary labor department statistics.

Total employment in all six Information industries is still about 11 percent less than it was in February before stay home orders began. The six industries, which employed about 2.9 million people in February, had lost about 315,000 jobs by June.

However, the June jobs report is the first indication that some Information industries may be joining the recovery from the pandemic that began last month for sectors like Construction and Retail.

This post describes changes in employment for all six Information industries from June 2019-June 2020. The post does not include employment in selected occupations, which can be found in last month's post on Information jobs.

The first chart shows aggregate employment in all six industries.

The chart (above) shows monthly changes in Information sector employment. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is seasonally adjusted to remove predictable influences such as seasonal changes or holiday hiring. This provides a more accurate estimate of changes from factors like the pandemic.

May and June employment statistics are preliminary and subject to revision.

The six Information industries employed more than 2.8 million people from June 2019-Feb. 2020. The industries lost jobs in March, April, and May before a small recovery in June.

June 2020 Information employment was still an estimated 315,000 jobs lower than in Feb. 2020, a decline of 10.9 percent. The Information sector employed an estimated 2.57 million people in June.

Information is part of the private, nonfarm business sector which employed 129.7 million people in February 2020. The sector lost an estimated 21 million jobs in April, then added jobs in May and June. However, in June the sector was still down 13.1 million jobs since February, a decline of 10.2 percent.

Subsequent charts report employment in each of the six Information industries.

The second chart (above) shows employment in Data Processing, which includes hosting and providing data processing services.

Data Processing had the largest employment increase from May to June, adding an estimated 5,600 jobs. Employment is now 345,500, which is still below the 349,600 jobs in February.

Total job losses since February are estimated to be 4,100, a decrease of 1.2 percent.

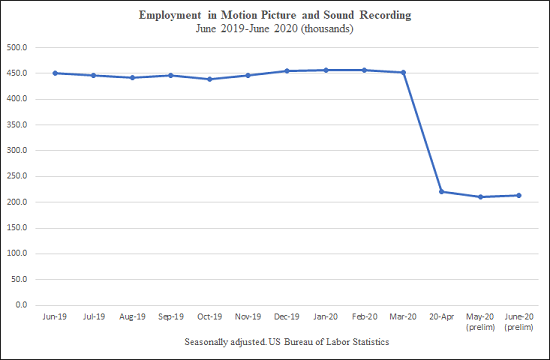

The third chart (above) shows Motion Picture and Sound Recording, which includes the production and distribution of motion pictures and sound recordings.

This industry had the second largest employment gain from May to June, adding an estimated 2,600 jobs. However, employment was still far below the February figure of 456,000.

Motion pictures and sound lost an estimated 243,700 jobs by June, or about 53.4 percent.

This unusually large decline may result from requirements that many people work in the same place when making a movie or a recording. Covid-19 makes physical proximity dangerous.

The fourth chart (above) shows Other Information Services, which includes search engines, internet-only publishing and broadcasting, and web sites that store and provide information.

This industry had the third largest employment gain from May to June, adding about 2,200 jobs.

Other Information jobs increased from February to March, before declining in April and May. Employment is still below the peak in March.

However, June's estimated employment figure is 1,200 higher than than the 354,400 jobs in February, an increase of 0.34 percent.

The fifth chart (above) shows Publishing, which includes newspapers, magazines, books, directories and software publishing.

Job losses slowed in in June when the industry lost an estimated 600 jobs, the largest monthly loss in the Information sector.

Publishing had 770,000 jobs in February and lost an an estimated 30,700 jobs by June, a decrease of 3.9 percent.

The sixth chart (above) shows Telecommunications, which includes distribution and services for telephones, cable and satellite broadcasting, and internet access.

Employment losses in Telecommunications also slowed, an estimated decrease of 300 jobs in June was the second largest monthly loss in Information.

The industry employed about 700,000 people in February. Telecommunications employment was down 12,400 June, an estimated decrease of 1.8 percent.

The seventh chart (above) shows Broadcasting, an industry that creates, acquires and distributes content via radio, television, cable and other subscription services.

Broadcasting employment decreased by an estimated 200 jobs in June, the smallest monthly loss in the Information sector.

The industry employed 263,300 people in February. Broadcasting lost an estimated 25,000 jobs by June, a decrease of 9.5 percent.

Comments

The pandemic continues to have the smallest effect on employment in Other Information Services, which may have two advantages. First, many employees can work from home. Second, there was increased demand for internet services as millions of people were ordered to stay home as much as possible.

The June increase in Data Processing jobs is consistent with continued or increased demand for technology-based products and services. Job losses in Telecommunications continued in June, perhaps because the widespread loss of income during the pandemic reduced demand for telephone and cable services.

Motion Picture and Sound Recording remains the hardest hit industry despite the gain of 2,600 jobs in June. This change is too small to say if the large-scale production of movies, television programs and recordings is starting to resume.

Publishing and broadcasting job losses slowed, but these industries did not recover in June.